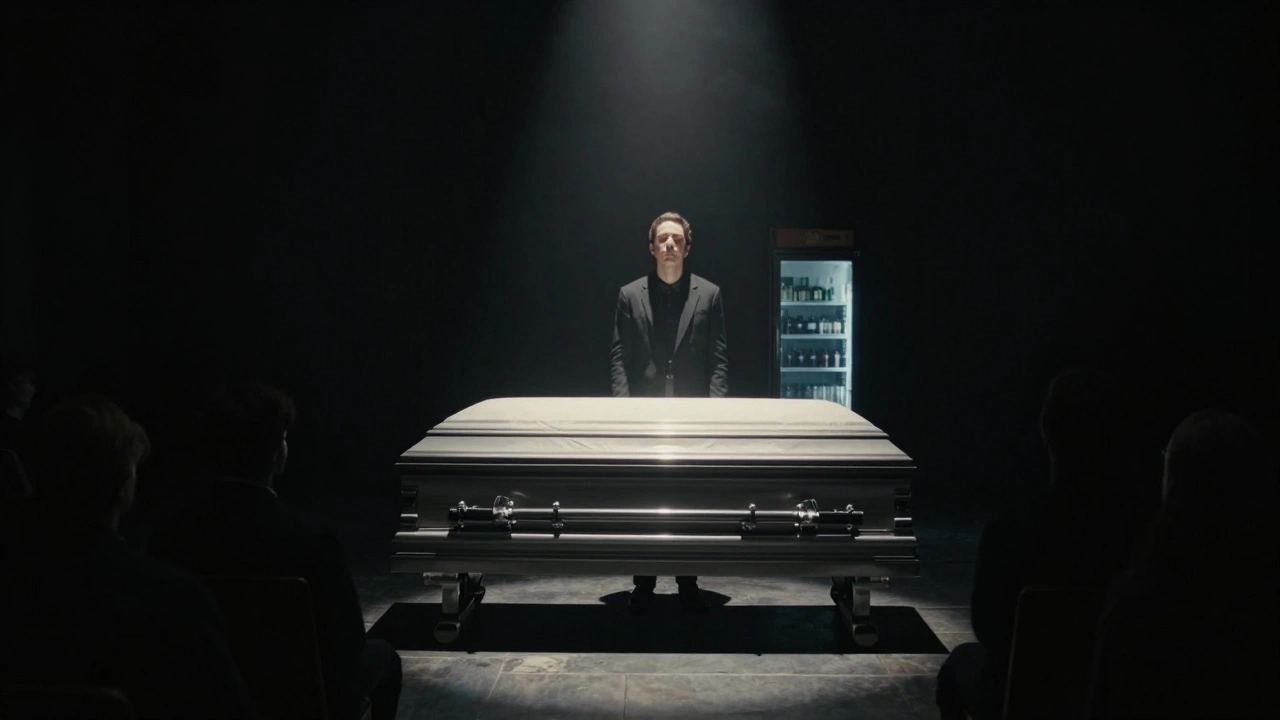

Most people avoid thinking about death. Alli Starr didn’t. At 12, she sat quietly in the back of her grandfather’s funeral service, not crying, not scared-just watching. The way the casket glowed under the chapel lights. The way the flowers smelled like earth and memory. The way people touched the coffin like it was still warm. That day, she didn’t see death as an ending. She saw it as a story waiting to be told.

The Quiet Observer

Alli grew up in a small town in Oregon where funerals were quiet affairs, handled by the same family-run funeral home for three generations. Her grandmother worked there as a seamstress, mending funeral gowns and arranging lace for the deceased. Alli would sit on the floor of the preparation room, watching her grandmother’s hands move like they were stitching together time itself. No one told her to leave. No one shushed her. She learned early that death wasn’t something to hide. It was something to honor.

By 15, she was volunteering at the funeral home, helping set up chairs, fold programs, and light candles. She didn’t want to be a mortician. She wanted to understand the silence between breaths. The weight of a hand left in a glove. The way a name carved into a headstone didn’t just mark a life-it held it.

From Caskets to Songs

Alli didn’t go to mortuary school. She went to art school. But her work never left the space between life and death. Her first album, Before the Last Breath, opened with a recording of her grandmother’s voice reading a eulogy she’d written for a stranger. The track was layered with the hum of a refrigeration unit, the rustle of linen, and the soft click of a casket latch closing. Critics called it haunting. Alli called it honest.

Her songs don’t talk about loss. They talk about presence. In Still Warm, she sings over the sound of a funeral home’s boiler turning on-a sound most people find cold. To her, it was comforting. It meant someone was being cared for. In What the Hands Remember, she samples the voice of a mortician who told her, "You don’t dress the dead to make them look alive. You dress them so they look like they’re sleeping in the best clothes they ever owned."

The Language of Care

Mortuary science isn’t about chemistry or anatomy alone. It’s about ritual. About touch. About the quiet dignity of washing a hand that once held a child, a cup of coffee, or a wedding ring. Alli learned this not from textbooks, but from listening. She spent months shadowing licensed funeral directors in five states. She didn’t take notes. She recorded voices. The way one director said, "I never call them "the body." I call them "Mr. Rivera" or "Ms. Chen."" The way another whispered, "I always leave the window cracked. They should have a breeze if they want it."

These moments became the bones of her storytelling. Her live performances include no instruments-just her voice, a single microphone, and a playback of real funeral home audio. The audience sits in dim light. No phones. No talking. Just the sound of a casket being lowered, a hymn played on a pipe organ, or a child asking, "Will Grandpa feel the rain?"

Death as a Teacher

Alli doesn’t romanticize death. She doesn’t call it beautiful. She calls it real. And in that honesty, she found a way to help people feel less alone. After one show in Seattle, a woman came up to her, trembling. "My mother died last week. I didn’t cry until I heard you play the sound of her favorite quilt being smoothed out. I didn’t know anyone else remembered that."

That’s the power of Alli’s work. She doesn’t try to fix grief. She doesn’t offer platitudes. She simply says: death is part of the story. And stories matter.

Her latest project, Voices of the Last Hour, is a collection of 47 audio portraits-each one built from interviews with people who worked with the dying: hospice nurses, funeral home staff, chaplains, even a man who spent 30 years driving a hearse. Each portrait ends with a single question: "What did you learn about love from saying goodbye?"

Why It Matters Now

In a world that sells you cremation urns shaped like dolphins and Instagram posts about "celebrating life," Alli’s work is a quiet rebellion. She doesn’t turn death into a trend. She turns it into a truth. Her music isn’t for the morbid. It’s for the human. The ones who still remember how to hold silence. Who still know that the most sacred thing you can do for someone who’s gone is to remember them exactly as they were-not as a symbol, not as a hashtag, but as a person who once laughed too loud, forgot their keys, or left socks on the floor.

Alli doesn’t tell you how to grieve. She just shows you how someone else did. And in doing so, she gives you permission to do it your way.

Is Alli Starr a mortician?

No, Alli Starr is not a licensed mortician. She never pursued formal training in mortuary science. Instead, she studied art and music, using her deep exposure to funeral homes and death care professionals as the foundation for her storytelling. Her work is informed by observation, listening, and emotional resonance-not professional certification.

What is soul storytelling?

Soul storytelling is a term Alli Starr uses to describe her approach to art that centers on the quiet, intimate moments surrounding death. Unlike traditional narratives that focus on loss or mourning, soul storytelling highlights presence, dignity, and the small, human details that remain after someone dies-the smell of a favorite sweater, the way a hand was placed, the sound of a casket closing. It’s storytelling that doesn’t try to fix grief but holds space for it.

Does Alli Starr use real audio from funeral homes?

Yes. Alli records real, unedited audio from funeral homes, hospice centers, and conversations with death care workers. She obtains explicit consent from everyone involved before using their voices or sounds. Her work is grounded in authenticity, not theatricality. The sounds you hear in her albums-the hum of refrigeration units, the rustle of linen, the click of a casket latch-are all genuine recordings.

How does Alli Starr’s work challenge modern views of death?

Modern culture often treats death as something to be sanitized, hidden, or turned into a trend-think "death positivity" as a hashtag or cremation urns as fashion items. Alli rejects this. Her work doesn’t glamorize death or make it cute. Instead, she brings attention to the physical, tactile, and emotional realities of death care. She shows that dignity isn’t in perfection-it’s in the ordinary, the messy, the human moments that happen when someone dies. Her approach invites listeners to sit with death, not run from it.

Where can I hear Alli Starr’s music?

Alli Starr’s music is available on major streaming platforms including Bandcamp, Spotify, Apple Music, and Amazon Music. Her albums Before the Last Breath and Voices of the Last Hour are also available as limited-edition vinyl and cassette releases through independent record labels that specialize in experimental and sound-based art. Live performances are held in small venues, art galleries, and funeral homes that partner with her project.

What Comes Next

If you’ve ever held someone’s hand as they took their last breath, or sat in a quiet room after a funeral, Alli Starr’s work might feel like a whisper you didn’t know you were waiting to hear. Her art doesn’t tell you how to feel. It just reminds you that you’re not the first to feel it-and you won’t be the last.

Death doesn’t need to be fixed. It needs to be witnessed.